How Do I Transfer a Family Member to a Different Nursing Home

- Enquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

Experiences and involvement of family members in transfer decisions from nursing home to hospital: a systematic review of qualitative research

BMC Geriatrics volume 19, Commodity number:155 (2019) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Background

Nursing home residents (NHR) are characterized past increasing frailty, multimorbidity and care dependency. These weather condition result in frequent infirmary transfers which can lead to negative effects on residents' wellness status and are often avoidable. Reasons for emergency department (ED) visits or hospital admissions are complex. Prior inquiry indicated factors influencing transfer decisions in view of nursing staff and general practitioners. The aim of this systematic review is to explore how family members experience and influence transfers from nursing home (NH) to hospital and how they are involved in the transfer decision.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in Medline via PubMed, Ebsco Scopus and CINAHL in May 2018. Studies were eligible if they contained information a) about the conclusion to transfer NHR to infirmary and b) the experiences or influence of family members. The review followed Joanna Briggs Institute'due south (JBI) arroyo for qualitative systematic reviews. Screening, selection and quality appraisal of studies were performed independently by two reviewers. Synthesis of qualitative information was conducted through meta-aggregation.

Results

After screening of n = 2863 articles, in total n = ten qualitative studies were included in the review. Results bespeak that family unit members of NHR experience controlling earlier hospitalization differently. They mainly reported NH-related, hospital-related, and family/resident-related factors influencing the transfer determination. The interest of family members in the controlling process varies - from no involvement to insistence on a decision in favor of their personal preferences. Still, hospital transfer decisions and other treatment decisions (e.chiliad. advance care planning (ACP) discussions) were commonly discussed with physicians and nurses. Conflicts between family members and healthcare providers more often than not arose effectually the interpretation of resident'due south best interest. In general, family members perceive discussions as challenging thus leading to emotional stress and discomfort.

Conclusion

The influence of NHR family members apropos infirmary transfer decisions varies. Family members are an important link for communication betwixt resident and medical staff and for communication between NH and hospital. Interventions aiming to reduce hospitalization rates have to have these findings into account.

Groundwork

Nursing home residents (NHR) are a vulnerable population group with circuitous intendance needs. Many of them suffer from chronic diseases and have functional disabilities [ane, ii]. Changes in resident's health status often lead to transfers from nursing domicile (NH) to hospital [3]. These transfers include sequent hospital admissions also as outpatient treatment in the emergency department (ED). The prevalence of transfer rates varies beyond different countries depending on health intendance system and enquiry design. Co-ordinate to a systematic review the incidence of transfers to EDs is at to the lowest degree 30 transfers per 100 residents per year [4]. A recent systematic review reported a range of infirmary admissions from 6.eight to 45.seven% for various time periods of follow-upwardly [5]. The gamble for hospital admissions increases in the last months of life [6,seven,viii,ix]. These results indicate that hospital transfers are common in NHR. A loftier proportion of these are judged as inappropriate or avoidable [x,11,12]. Negative effects are in-hospital complications (e.thou. pressure ulcers, nosocomial infections), functional refuse, delirium and costs of increased health intendance utilization (e.k., for transport, examination, diagnosis and therapy) [11]. Reasons for hospital admission are often complex and multicausal. Most important factors associated with hospitalization are - for example - clinical conditions similar cardiovascular events, falls and infections [iii, 11] or system-related factors similar staffing capacity, lack of qualification, physician'south availability or necessary equipment in the NH [xiii,xiv,15].

In recent years, several reviews aimed to explore factors influencing the transfer determination. These reviews analyzed the transfer process in view of nursing staff and general practitioners [thirteen, fourteen, xvi]. Several studies indicated that family members may play an important role in the NH, for example in the timely detection of changes in NHR'southward wellness status [17] or interim as decision maker for the resident in example of dementia [18]. Yet, until now there does non be an overview summarizing the perspectives of family members. This review aims to close this gap in the literature and summarizes family members' experience and perceived interest in the decision to transfer a NHR to hospital.

Methods

The review followed the guideline of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence [xix]. For the purpose of this review we defined a nursing home equally a facility providing long-term nursing care for older people permanently living there. Hospitalization or infirmary transfer (both terms are used synonymously here) was defined as a planned or an unplanned admission to hospital or ED visit. This contained too end-of-life admissions in case of an acute or palliative deterioration. With the term family members nosotros defined the primary contact persons of NHR who are authorized to take decisions for them, e.g., partners, children (but also close friends or others). We used the term 'relatives' as a synonym.

Eligibility criteria

We considered studies every bit eligible if they ane) had a qualitative or mixed-methods research design, 2) contained data most decision-making of hospitalization from NH and 3) described the experiences or involvement of family members. All publication types, except of instance studies, study protocols, and editorials, were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if they did not provide any information almost the grade of family members' interest (for example, quantitative studies just presenting statistical associations between hospitalizations and family unit members or studies which just described the presence of bachelor relatives). Studies were besides excluded if they were related to other intendance settings (brusk-term care, assisted living facilities and dwelling house care).

In the full text screening we included studies which straight included family members equally report participants. Because we intended to investigate the conclusion-making process in the NH before hospitalization, results related to the situation after returning dorsum to the NH were not included.

Literature search

The Cochrane Handbook recommends three bibliographic databases as the about important sources to search for potential studies (Cardinal, MEDLINE, EMBASE) in systematic reviews [20]. Considering CENTRAL focuses on trials which were not eligible for our review question, we chose CINAHL as nursing-related database instead. Searching in SCOPUS included most EMBASE content. We conducted systematic literature in Medline via PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Centrolineal Health Literature (CINAHL) and Ebsco Scopus on 30 May 2018.

Based on objective of the review and the PiCo template for qualitative reviews [21], the search combined sets of terms for Population (family members), the phenomenon of Interest (hospitalization) and the Context (nursing home) using MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) and text words (encounter Additional file 1 for literature search strategy). Keywords for the search strategy were derived from an initial limited search in Medline via PubMed. In addition, the search strategy of a thematically similar published review [5] was used and complemented for the purpose of this article. Manual search was performed on reference lists of articles for additional fabric. Further, we used Google Scholar to identify grey literature past combining the terms "nursing dwelling", "hospital", "transfer/access" and "family/relatives". There was no limitation in time period to identify all relevant literature. Language was no exclusion criteria.

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed independently by ii reviewers (AP, AF) using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Inquiry [22]. Disagreements between reviewers were solved by discussion and if no consensus could be found, results were discussed afterwards independent assessment of a third reviewer (GS). Results of quality assessment are shown in Additional file two.

Information extraction

Data relevant to the review question were extracted from the included studies using an adapted version of the data extraction tool from JBI Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) [19]. Following information were extracted: authors, year, country, written report focus/phenomen of involvement, method of information collection, method of data assay, participants, setting and key findings (Table i). The first reviewer (AP) conducted data extraction for each written report and was checked by a second reviewer (AF).

Data synthesis

For managing data synthesis we used the software MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2018. Articles were analyzed independently past two persons to develop a list of thematic codes and subcodes (open coding). The codes were not specified prior to analysis and therefore derived from the text solely. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until consensus led to a final code list. The articles were then re-analyzed using this list.

Based on the JBI guide for information synthesis [19] meta-aggregation was used to synthesize qualitative information. The following three steps were conducted: ane) all text passages and quotes relevant to the review question were extracted from the results, discussion and conclusions of each study (also in the abstract). The illustrations were synthesized to findings which were rated according to JBI-QARI levels of credibility (U=Unequivocal; C=Credible; NS=Not supported). two) Findings were summarized to categories and subcategories based on similarity in meaning. 3) Synthesized findings were derived from the categories. Data synthesis was performed by the first reviewer (AP). As validation, the analysis of findings was discussed with the other authors.

Results

Screening and search outcome

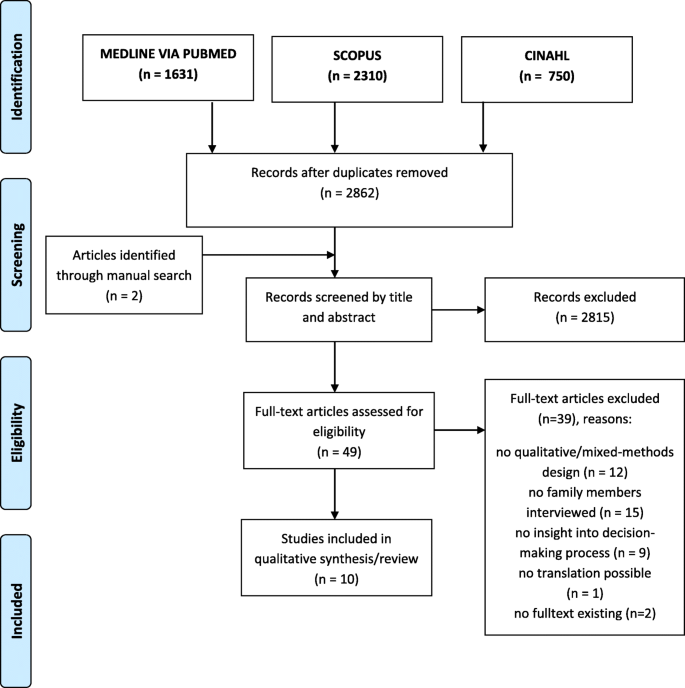

The primary literature search identified 4691 articles. Additionally, northward = 2 articles were plant through manual search. Afterwards removing duplicates ii researchers (AP, AF) independently screened title and abstruse of n = 2862 articles using the software tool Rayyan [23]. Any potentially relevant publication (n = 49) was ordered in full-text and assessed for inclusion and exclusion according to eligibility criteria, following the aforementioned procedure. After total-text screening n = 39 studies were excluded, i of them because translation of a Japanese paper was not possible (see Additional file 3 for list of excluded studies). Whatever disagreement in the procedure of pick and assessment was solved past discussion and if necessary by a third researcher (GS). In total north=10 studies were included in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Written report selection and screening process

Description of included studies

The included studies (Table 1) were published between 1989 and 2016, most of them later 2010. Iv studies were conducted in the USA [24,25,26,27], two each in Canada [28, 29] and Commonwealth of australia [30, 31], and one each in Norway [32] and kingdom of the netherlands [33]. Eight studies used semi-structured interviews, in-depth interviews or focus groups.

2 studies conducted a mixed-methods pattern combining participant observation and interviews [25] or combining interviews and quantitative assay [26]. Eight studies used qualitative design. Information were analyzed using thematic, content or comparative assay or is just described as "qualitative assay" [25]. The studies focused on the family members' perspective on astute changes in residents' wellness status, the decision-making procedure effectually infirmary transfers, influencing factors and dealing with stop-of-life care, death or limited prolonging treatment. Referring to the inclusion criteria, participants of the studies were family members only [24, 27, 32] or a combination of family members and residents, nurses, physicians or other healthcare providers (n = viii) [25, 26, 28,29,thirty,31, 33]. Referring to our wide definition of "family members", none of the studies included perspectives of shut friends, neighbors or others.

Quality of studies

Using JBI-QARI tool the critical appraisal showed variation in the quality of the 10 included studies. The percentage of quality criteria answered with 'yes' varied between four of 10 (40%) and ix of 10 (90%) in each written report (run across Additional file 2). Referring to the objectives all studies used appropriate methods to answer their research question. Most studies represented participants' voices adequately through quotations, except 1 [25]. However, most of the studies did non provide a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically. The influence of the researcher on the inquiry was addressed in none of the studies. One written report did non provide information nigh ethical blessing [25]. In decision the quality of the included studies can exist rated as moderate to high.

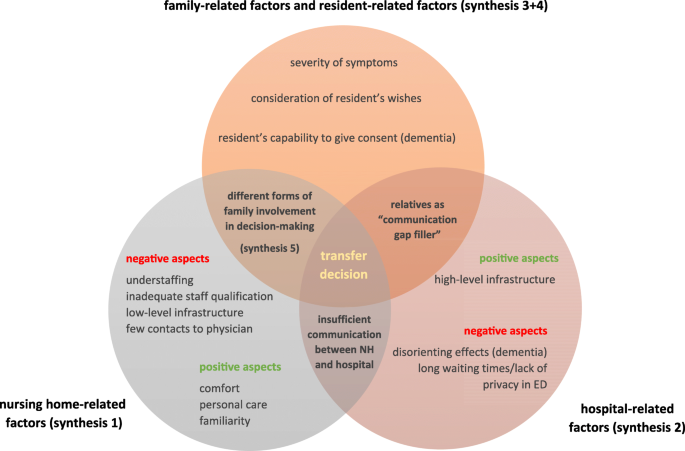

Findings and categories

Lxx-four illustrations were extracted from the 10 included studies. These were analyzed and grouped into 18 categories based on similarity in meaning. The categories were amassed into 5 synthesized findings: 'nursing habitation-related factors (synthesis 1), 'hospital-related factors (synthesis 2), 'family unit-related and resident-related factors' (synthesis three + 4) and 'forms of family involvement' (synthesis 5) (Fig. two).

Factors influencing hospital transfer determination - overview of family members' experiences

Synthesized findings

Synthesis 1: transfer decision is affected past family unit members' judgement of quality of NH intendance (nursing-home related factors)

This synthesized finding emerged from two categories: positive NH experiences and negative NH experiences. Depending on how family members perceive daily care in the NH or which expectation they have, their trend to hospitalize their older relative tin can differ. On the 1 manus family members favored the "personal care" [28] in the NH and associated it with "familiarity" [24] and "comfort" [24, 28] which had a positive bear upon on "quality of life" [24]. Robinson et al. (2012), for example, concluded in their report: "When family unit members observed healthcare providers treating their relatives with compassion, nobility and respect, their relationships with healthcare providers were supported by trust, confidence and admiration" [29]. These factors seem to be beneficial for remaining in the NH and avoiding hospitalization.

On the other manus studies described several negative experiences in the NH: family members argued that particularly understaffing [28, xxx, 31] is problematic when NH staff is not able to react speedily plenty to resident'due south changes in wellness condition [24]. Also the qualification of NH staff [25, 31] is a primary business organization when a change in resident's health status occurs. In this context, family members sometimes observed "risk-averse" beliefs when nursing staff "has to cover themselves. Overreaction is probably the incorrect discussion but they're overcautious" [30]. Kayser-Jones et al. (1989) even concluded that "families reported feeling frustrated past what they identified as inadequate nursing skills and, fearful when their relative's condition worsened, sometimes urged the physician to transfer him/her to an acute hospital" [25]. Too that, family unit members criticized the lack of medico's availability, [24, 30, 31] and necessary equipment in the NH [28]. In summary, these impressions led to the opinion that NH just can provide low-level care which increases the take a chance of hospitalization [24].

Synthesis ii: transfer decision is affected past family members' judgement on quality of hospital care (infirmary related factors)

Family unit members who had negative experiences in the NH, concurrently talked about their positive attitude towards hospital treatment. "If we hadn't had a skillful hospital experience, nosotros might have been more than influenced to stay hither [comment of the authors: in the NH]" [26]. The most oft mentioned benefits of hospital intendance were bachelor medical equipment and infrastructure [24, 28]. Ane family member who decided about place of care for his relative with pneumonia pointed out: "[In the infirmary] information technology'southward not a question of taking claret, sending it to the laboratory and having somebody come back three days afterwards... they immediately check it and they know exactly [what is going on] "[28]. Other family members besides advocated "more care around the clock" in the infirmary [26].

Particularly in the case of dementia hospital treatment tin can take a "disorienting effect" [xxx], can cause "confusion" [28] because of "lack of attention to the needs of aged patients with cerebral or functional impairments" [24]. In these cases family members tended more than to avoid hospitalization. 'To transfer [my female parent] to hospital and go utilise to the infirmary environment, I retrieve is more detrimental...[even though] I call back they would get more superior treatment in the hospital... and the medical staff cess in that location would be far superior than in the nursing dwelling' [28]. But besides regardless of a dementia diagnosis, some family unit members described hospital transfers as a "trauma experience […] without adequate explanation, to an unfamiliar location, with unfamiliar staff and an unfamiliar physician" [25]. Specially in the ED "waiting times" and "lack of privacy and cool ambience temperature" [30] led to discomfort influencing family members' attitude towards hospitalization.

Synthesis 3: perceived severity of clinical situation effects the transfer determination (family unit-related and resident-related factors)

The tendency to transfer the relative to hospital depended also on severity of symptoms. Family members favored infirmary transfers when "a dramatic alter in the person's status" occurred [27]. "Hospital care is clearly necessary for some conditions (e.grand. fainting, broken basic, operations, and heart problems)" but for instance, "not for pneumonia" [28]. In this context 1 written report indicated that if the reason for transfer was viewed as "not-life threatening", advance directives were not considered and seen by the family unit as not "applicable to the situation" [24]. But severity of symptoms is not always clear. Kayser-Jones et al. (1989) argued: "Transfers besides occurred when there was uncertainty virtually the severity of the patient's condition. In such cases, specially if a concerned family member was present, physicians hospitalized the patient out of indecision and/or fright of litigation" [25].

Synthesis 4: knowing, accepting and upholding resident wishes are challenges for family unit members (family-related and resident-related factors)

In the included studies family members dealt differently with resident'southward preferences. Some of them knew the wishes of their older relative, others did not. If the residents' wishes were unknown, this is because talking about expiry "was a sort of taboo " inside the family [32]. Often transfer or treatment decisions were discussed with family members [24, 27, 29, 30], but really they felt uncomfortable in their function every bit decision makers. Van Soest-Poortvliet et al. (2015) for example showed that willingness to hash out end of life situations can be express and summarized: "Some families are open for discussions about the end of life and it is non hard to brand decisions. However, other families have to become used to the NH. They absolutely did not want discussions about stop of life immediately" [33]. In single cases there may be relatives who either do not recognize cease of life-symptoms (e.grand. resident stops drinking) [32] or suppressed the fact that their loved one is approaching death [27]. The nurse said, "Maybe she should exist nether hospice care." I said, "Oh definitely. No problem with hospice." But that was like a lightning commodities and the first time I actually idea, "Oh my gosh, she's dying" [27].

If resident's wishes were known, relatives reported that upholding these wishes can exist very challenging, for instance if relatives did non concord with them [24, 27, 30]. On the other manus, Dreyer et al. (2009) described the tendency of some family members to override resident's wishes. This may happen when residents – independent from being able to give consent or not – refused to be fed. Equally a consequence, family members forced their loved 1 to eat or to drink. The authors pointed out in this context: […] not all the relatives acted in the patient's best interests. […] personal preferences, feelings and viewpoints could boss. Some wanted life-prolonging treatment considering they were afraid of the loss they would experience. Others had lost one of their parents before, had not done plenty for the dying parent then, and wanted to practice "everything possible so that they would not exist left with a bad conscience again" [32].

Synthesis 5: the extent of family members' involvement in handling and transfer decisions vary (forms of family unit interest)

In daily care of NHs handling decisions and hospital transfer decisions are often required. Family members are differently involved in this controlling procedure – from no interest to insistence of several family members' to determine in favor of their personal preferences. Dreyer et al. (2006), for example, described that relatives were often not contacted until the health status of their loved ones deteriorates. Especially in case of dementia and when acute events occurred (due east.g. suspected stroke) physicians and nursing staff decided about hospital transfers without discussion with the family [32].

Nevertheless, in daily care family members have most contacts with nurses. Some relatives reported that they completely trust in the medico'due south and staff'south medical know-how and therefore ceded/delegated decisions to them [26, 30] - "I wouldn't decide anything. I would talk to the doctor. To tell yous the truth, I would tell them, if they experience that they tin do it here that is alright or either conduct her to the hospital. Information technology'southward up to them. I wouldn't try to dominate them too much" [26]. Despite the reporting of family unit members that a contact with physicians in the NH were oftentimes missing [24, xxx], several studies showed that physicians and nursing staff discussed treatment or hospital transfer decisions together with the resident and the family unit if that was desired [28,29,30, 32, 33]. In instance of an acute and "urgent" situation [29] it was also considered acceptable to inform the relatives immediately later on hospital transition. Also advance intendance planning (ACP) discussions usually took place prior to the hospitalization [24]. Van Soest-Poortvliet et al. (2015) reported that discussions about hospitalization and resuscitation more often than not took place direct or soon after admission. They were often initiated by the doc and resulted in practice-not-resuscitate (DNR) and a do-not-hospitalize (DNH) orders. During these discussions some family members stated to feel "uncomfortable" [29] in their role, peculiarly when they had a lack of medical knowledge [29]. Waldrop et al. (2011) suggested: "decisions that occurred in the heat of the moment were painful and difficult for family members" [27]. Therefore, most relatives were commonly thankful for recommendations and took staffs' advice [28,29,30]. "They felt they needed to phone call the ambulance and go her dorsum there. And they said how do you feel nearly that? Tin we call the ambulance and get her dorsum there? And I said if you feel she needs the ambulance – needs infirmary – to become back there, please do [relative 11]" [30]. In this context, Robinson et al. (2012) pointed out that involvement of the family unit is highly influenced past the relationship between the family and the NH staff/physicians. On the one mitt, family members were valued as of import and supportive key members in decision-making [29]. In the transition process information about the resident and her/his medication sometimes got lost [24]. Family unit members were able to "fill in the gaps" [29] in the advice betwixt the NH and the infirmary: "For example, family members were critical to helping ED providers 'know' the resident and sometimes provided the merely report to NH staff virtually what happened in the ED" [29].

On the other hand, in some cases the determination making-process of infirmary transfers or ACP discussions can cause conflicts between relatives and NH staff [25, 27, 29, 32]. Tensions occurred "typically around interpretation of the resident's best interests and discrepancies in perspective" [29]. Such conflicts appeared when family unit members disagreed with the medico's recommendation of a transfer because their loved one did not want to go to the hospital. On the contrary, when nursing staff believed that "it was in the resident'southward all-time interest to remain 'at domicile', peculiarly family unit members "at a geographic altitude [...] wanted 'everything done'" for their relative" [29]. Conflicts can besides arise when family unit members felt "frustrated by what they identified as inadequate nursing skills" and were "fearful when their relative'southward condition worsened" [25]. In all these cases pressure/insistence from the family tin can influence infirmary transfers or ACP decisions.

Discussion

Many studies examined influencing factors on transfer decisions from NH to infirmary. Almost of them reported the decision-making process in the perspective of nursing staff and physicians. This review aimed to extend the existing evidence by analysing experiences and involvement of family members when a hospital transfer decision occurs. Because of thematic similarity the studies did non only deal with hospital transfer decisions, but also with end-of-life decisions like limited prolonging treatment and ACP.

Being confronted with treatment or transfer decisions family members often reported a lot of discomfort and emotional stress. Even though residents reported to trust relatives making decisions for them [34], relatives themselves felt insecure in these situations. Especially if the older residents are unable to give consent (eastward.g. in example of dementia), if their wishes are unknown or practice not correspond with relatives' preferences, these situations are perceived as very challenging. There can be reasons to believe that decisions fabricated by family members tend to correspond more than their own wishes rather than the preferences of the resident [35]. Therefore, some situations might crusade conflicts betwixt relatives and nursing staff in the word of resident's all-time interests. The existence of accelerate directives might non be sufficient to solve this problem because 1) just few residents possess advances directives [36] and often they are incomplete [37] and 2) therefore many residents were yet transferred to hospital despite of having a DNH-order [38, 39]. The results of our review indicate that interventions trying to forestall hospital admissions should take into business relationship the influence of relatives. As Dreyer et al. (2009) reported, relatives fear death/losing a loved one or alive with bad conscience. Cohen et al. (2017) described like aspects when guilt pushes families to "do everything" which includes hospitalization: "Essentially people will say that yous're giving upwardly. 'Y'all mean y'all didn't send her this time? Y'all gave upward'" [40]. Physicians just rarely discuss psychological (due east.g. sadness and fright of decease), spiritual or existential problems (e.g. difficulty in accepting the state of affairs) with residents and relatives during the last months earlier death [41]. Intensive discussions at NH admission about treatment preferences, concerns amd regular support of a social worker/pastor/chaplain might exist helpful responding to relatives' needs of advice and information. Further inquiry is needed analysing if such interventions may accept an affect on hospital transfer rates.

Besides that, nosotros found that the attitude of family members towards hospital transfers mainly depends on their private positive and negative experiences regarding NH and hospital intendance. If personal intendance is desired, relatives assume that the NH is the more suitable setting for further treatment. On the other hand, family members tend to accept hospitalization if they acquaintance 1) hospital care with quick medical examination and loftier-level infrastructure and 2) NH care with understaffing, insufficient staff qualification or lack of physician's availability. These aspects corresponded with reporting of nursing staff in other studies [14, fifteen, 42,43,44]. In addition, general practitioners stated that clinical movie, doc-legal issues, workload [45] and advice between healthcare professionals increment the tendency for hospitalization [46]. Comparison relatives' experiences to the statements of medical staff, it seems to be that both perceive the same problems when talking about hospital transfer decisions.

Family unit members described their extent of involvement in decision making very differently. A study of Petriwskyj et al. (2014) explored family unit involvement in decision-making explicitly focusing on residents with dementia – the results mainly represent with our review showing that participation of relatives varied from total control to delegating the determination to medical staff [18]. Across the included studies in this review, relatives reported to discuss treatment and transfer conclusion with the physician (and sometimes the resident). Family members argued non being able to assess residents' complaints - and therefore relying completely on the expertise of medical staff taking their communication/handling recommendations. This was also shown by a study in Norway [47]. Even so, nursing staff considered family members playing a key role because they oft deed as "gap filler" betwixt NH and hospital when information gets lost during transfer. Manias et al. (2015) described in this context that family members are, for example, able to solve medication-related problems in the hospital when previously beingness involved in medication activities at home [48]. Relatives can also exist an important link between the resident and the nursing staff - for example by noticing timely signs of changes in health status and informing or educating nursing staff nearly these changes [17].

Strengths and limitations of the review

To the best of our knowledge this is the beginning systematic review which focuses on the experiences of family unit members and gives an overview of their involvement in the controlling process of hospitalization. Merely three of the 10 studies focused on family members solely [24, 27, 32]. The other studies interviewed also residents and/or other healthcare providers and summarized their findings beyond all participants. The extraction of family members' perspectives was therefore less accurate which might be a limitation. To minimize the chance of biased results and overlooking relevant text passages, information extraction was conducted independently by ii reviewers and extended to the results, word and abstract for each written report. Because data analysis was conducted based on published research articles (without the original transcripts), coding of the text passages was mainly dependent on the quality of the codings in the original articles.

Most of the included studies had relevant methodological shortcomings, for example the study by Kayser-Jones et al. (1989) [25] reached in the assessment merely a score of twoscore%. However, the contained data are concordant to the results of other included studies. The cultural and theoretical groundwork of the researcher might influence the results of the studies. The included studies neither provided information on the researchers' background nor discussed these aspects further. Equally scientific backgrounds of the authors differ, we assume that these limitations are unlikely to influence the results of our review.

The effects of potentially influencing factors like NH ownership or health organisation-related characteristics were non described in the included studies. In addition, majority of the studies were conducted in the USA, Canada and Australia. Therefore, the results are express to Western countries and especially to Northern America and Australia.

Conclusion

The results of this review evidence that relatives' perceptions of transfer and treatment decisions are mainly influenced by positive and negative care experiences in the NH and hospital, individual preferences and the human relationship betwixt nurses, relatives and physicians. Involvement of family members in controlling varies from no involvement to total control well-nigh decisions. Generally, beingness confronted with hospitalization decisions and cease-of-life issues is very stressful and challenging for relatives. Nevertheless, family unit members are an of import link betwixt resident and medical staff also every bit between NH and hospital. These insights should be taken into account when developing interventions to reduce infirmary transfers from NH. Further enquiry, especially in European countries is needed to examine generalizability of the results on other populations.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the respective author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACP:

-

Accelerate care planning

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- DNH order:

-

Do-not-hospitalize order

- DNR guild:

-

Do-not-resuscitate guild

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- JBI-QARI:

-

JBI Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- NH:

-

Nursing home

- NRH:

-

Nursing habitation residents

References

-

Gordon AL, Franklin K, Bradshaw L, et al. Health status of UK care home residents: a cohort written report. Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):97–103.

-

Kojima G. Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(11):940–5.

-

Grabowski DC, Stewart KA, Broderick SM, et al. Predictors of nursing home hospitalization: a review of the literature. Med Intendance Res Rev. 2008;65(1):three–39.

-

Arendts 1000, Howard Yard. The interface between residential aged care and the emergency department: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39(3):306–12.

-

Hoffmann F, Allers K. Age and sex differences in hospitalisation of nursing abode residents: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;vi(10):e011912.

-

Allers K, Hoffmann F. Bloodshed and hospitalization at the end of life in newly admitted nursing home residents with and without dementia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(eight):833–9.

-

Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing dwelling residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–21.

-

Miller SC, Dahal R, Lima JC, et al. Palliative intendance consultations in nursing homes and stop-of-life hospitalizations. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;52(half-dozen):878–83.

-

Ramroth H, Specht-Leible Due north, Konig HH, et al. Hospitalizations during the final months of life of nursing home residents: a retrospective cohort written report from Frg. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:70.

-

Cardona-Morrell M, Kim JCH, Brabrand M, et al. What is inappropriate hospital use for elderly people about the end of life? A systematic review. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;42:39–50.

-

Dwyer R, Gabbe B, Stoelwinder JU, et al. A systematic review of outcomes post-obit emergency transfer to hospital for residents of aged care facilities. Historic period Ageing. 2014;43(half-dozen):759–66.

-

Renom-Guiteras A, Uhrenfeldt L, Meyer Thou, et al. Assessment tools for determining appropriateness of admission to acute intendance of persons transferred from long-term care facilities: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:80.

-

Arendts Grand, Quine South, Howard G. Decision to transfer to an emergency department from residential aged care: a systematic review of qualitative research. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(four):825–33.

-

Laging B, Ford R, Bauer Grand, et al. A meta-synthesis of factors influencing nursing habitation staff decisions to transfer residents to infirmary. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(10):2224–36.

-

Trahan LM, Spiers JA, Cummings GG. Decisions to transfer nursing dwelling house residents to emergency departments: a scoping review of contributing factors and staff perspectives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(11):994–1005.

-

O'Neill B, Parkinson L, Dwyer T, et al. Nursing habitation nurses' perceptions of emergency transfers from nursing homes to hospital: a review of qualitative studies using systematic methods. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36(vi):423–30.

-

Powell C, Blighe A, Froggatt K, et al. Family interest in timely detection of changes in health of nursing homes residents: a qualitative exploratory written report. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1–2):317–27.

-

Petriwskyj A, Gibson A, Parker D, et al. A qualitative metasynthesis: family involvement in decision making for people with dementia in residential anile intendance. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2014;12(2):87–104.

-

Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, et al. Chapter two: systematic reviews of qualitative testify. In: Reviewers' Manual. Edited by Aromataris E, Munn Z. (editors), The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Available from https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/Transmission/.

-

Higgins JPT, Dark-green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]; 2011. Available from https://grooming.cochrane.org/handbook.

-

Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(four):53–half dozen.

-

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt M. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–87.

-

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan - a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(210).

-

Abrahamson K, Bernard B, Magnabosco 50, et al. The experiences of family members in the nursing habitation to hospital transfer conclusion. BMC Geriatr. 2016;sixteen(ane):184.

-

Kayser-Jones JS, Wiener CL, Barbaccia JC. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of nursing dwelling residents. Gerontologist. 1989;29(iv):502–10.

-

Tappen RM, Elkins D, Worch S, et al. Modes of determination making used past nursing dwelling house residents and their families when confronted with potential hospital readmission. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(6):288–99.

-

Waldrop DP, Kusmaul Due north. The living-dying interval in nursing home-based end-of-life care: family unit caregivers' experiences. J Gerontol Soc Piece of work. 2011;54(eight):768–87.

-

Carusone SC, Loeb M, Lohfeld L. Pneumonia care and the nursing home: a qualitative descriptive study of resident and family member perspectives. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:ii.

-

Robinson CA, Bottorff JL, Lilly MB, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on transitions of nursing home residents to hospital emergency departments and back in ii Canadian provinces. J Aging Stud. 2012;26(4):419–27.

-

Arendts Grand, Popescu A, Howting D, et al. They never talked to me about... ': perspectives on aged care resident transfer to emergency departments. Australas J Ageing. 2015;34(ii):95–102.

-

Arendts G, Reibel T, Codde J, et al. Tin can transfers from residential aged intendance facilities to the emergency section exist avoided through improved principal care services? Data from qualitative interviews. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29(2):61–5.

-

Dreyer A, Forde R, Nortvedt P. Autonomy at the end of life: life-prolonging handling in nursing homes--relatives' function in the decision-making process. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(11):672–7.

-

van Soest-Poortvliet MC, van der Steen JT, Gutschow Thousand, et al. Advance care planning in nursing home patients with dementia: a qualitative interview study amidst family and professional caregivers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;xvi(11):979–89.

-

Bollig Grand, Gjengedal Eastward, Rosland JH. They know!-do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on accelerate intendance planning, end-of-life care, and conclusion-making in nursing homes. Palliat Med. 2016;xxx(5):456–seventy.

-

Fagerlin A, Ditto PH, Danks JH, et al. Projection in surrogate decisions about life-sustaining medical treatments. Health Psychol. 2001;twenty(3):166–75.

-

Tjia J, Dharmawardene M, Givens JL. Advance directives amid nursing abode residents with mild, moderate, and advanced dementia. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(1):16–21.

-

Sommer Southward, Marckmann Thousand, Pentzek M, et al. Advance directives in nursing homes: prevalence, validity, significance, and nursing staff adherence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(37):577–83.

-

Perry South, Lawand C. A snapshot of advance directives in long-term care: how frequently is "do non" done? Healthc Q. 2017;xix(4):x–2.

-

Cohen AB, Knobf MT, Fried TR. Do-not-hospitalize orders in nursing homes: "call the family instead of calling the ambulance". J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1573–seven.

-

Cohen AB, Knobf MT, Fried TR. Avoiding hospitalizations from nursing homes for potentially burdensome care: results of a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):137–9.

-

Morin L, Johnell M, Van den Cake L, et al. Discussing end-of-life bug in nursing homes: a nationwide written report in France. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):395–402.

-

Kirsebom M, Wadensten B, Hedstrom 1000. Communication and coordination during transition of older persons betwixt nursing homes and hospital still in need of comeback. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(4):886–95.

-

O'Connell B, Hawkins M, Considine J, et al. Referrals to hospital emergency departments from residential aged care facilities: stuck in a time warp. Contemp Nurse. 2013;45(2):228–33.

-

Shanley C, Whitmore Eastward, Conforti D, et al. Decisions about transferring nursing dwelling residents to hospital: highlighting the roles of advance care planning and back up from local hospital and community wellness services. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(19–20):2897–906.

-

McDermott C, Coppin R, Piffling P, et al. Hospital admissions from nursing homes: a qualitative study of GP decision making. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(601):e538–45.

-

De Korte-Verhoef MC, Pasman HR, Schweitzer BP, et al. Full general practitioners' perspectives on the avoidability of hospitalizations at the terminate of life: a mixed-method study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(7):949–58.

-

Gjerberg E, Lillemoen Fifty, Forde R, et al. Terminate-of-life care communications and shared determination-making in Norwegian nursing homes--experiences and perspectives of patients and relatives. BMC Geriatr. 2015;fifteen:103.

-

Manias E. Communication relating to family unit members' involvement and understandings about patients' medication management in hospital. Wellness Expect. 2015;xviii(5):850–66.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros give thanks the following members of the research team for commenting on the manuscript: Falk Hoffmann, Michael Freitag and Ove Spreckelsen. Special thanks to Katharina Allers for her support in developing the search strategy. Nosotros admit the contribution of Imke Seifert who assisted in coding and analysis of data.

Funding

This review was developed every bit part of the project 'HOMERN' focusing on hospitalizations and emergency section visits of nursing home residents in Germany. The project is funded by the Innovation Fund coordinated by the Innovation Commission of the Federal Joint Committee (Yard-BA) in Germany (grant number: 01VSF16043) which had no influence on the content of the paper and the publication procedure.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

AP, AF and GS developed the concept and design of this systematic review. Search strategy was developed past AP and was tested by AF and GS. AP performed the literature search. Screening, pick and data extraction was conducted by AP and AF. Quality appraisal and analysis was performed by AP, AF and GS. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript critically and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics blessing and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Pulst, A., Fassmer, A.Thousand. & Schmiemann, G. Experiences and interest of family unit members in transfer decisions from nursing home to infirmary: a systematic review of qualitative inquiry. BMC Geriatr 19, 155 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1170-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1170-seven

Keywords

- Nursing home

- Hospitalization

- Patient transfer

- Decision making

- Family unit

- Qualitative evidence synthesis

Source: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1170-7

0 Response to "How Do I Transfer a Family Member to a Different Nursing Home"

Post a Comment